Last Updated on November 7, 2025

I’ve genuinely enjoyed using Canon’s EOS 650, and I don’t regret the purchase, but I couldn’t enthusiastically recommend it for the majority of today’s film shooters. The 650 is a perfectly fine camera for those who want to dip a toe in 35mm photography and are on a tight budget, shoot in an automatic mode, and already have a collection of EF lenses. If, however, you love shooting fully manual and want a more “authentic” old-school film experience, look elsewhere. That said, camera collectors of all types may want to pick up a 650 simply because of its interesting historical value: it’s the first Canon camera with an EF mount.

Spec Summary

Format: 35mm.

Dates: Manufactured from March 1987 to February 1989. So any 650 you buy today will be older than Nirvana’s Nevermind. And smell like anything but teen spirit.

Current cost and availability: I got mine seven years ago for 69 bucks from a proper camera shop that (in theory) checked it out and graded it in nearly new shape. On eBay, you can readily find them anywhere from $10 to $90 (but buyer beware on the camera’s actual condition). B&H, Adorama, and KEH sometimes have them in their used stock too.

Price update 2023: Prices for the 650 have thankfully remained pretty stable! You can find one, like I did, for $70 all day long.

Price update 2024: Holding steady at a reasonable $60 to $80.

Price update 2025: Despite the absolutely galling price inflation for 35mm cameras during the past few years, the 650 is a bargain at around 70 bucks for a copy in good shape. It’s by no means the most satisfying-to-use film camera still available, but it’ll get the job done at a price that remains reasonable.

Autofocus: Yes. And this is the camera that really started it all off for Canon. It features a single, centered autofocus point that for the time was considered quite mighty.

Lens mount: EF. Lenses are thus super easy to find in every price range used and new. There are literally millions of EF lenses out in the wild.

Battery: The camera takes a single 2CR5. You can get them from Amazon, Best Buy, Walmart, and so on, but they don’t seem to be quite as available or cheap as they used to be. They are rated to last about 40 rolls, which feels right though I haven’t actually counted. They also can be stored in the camera for a long while without dying. I had my 650 packed away for about a year, and the battery fired up just fine.

Weight and construction: 660 grams or 1.45 pounds or a little over two of Canon’s 50mm f/1.4 lenses. It’s made of the usual engineering plastic (like a contemporary Rebel), so the weight is very manageable. But you don’t want to have fumbly fingers over concrete.

Light meter: Yep, it has one, and if you’ve used a current Canon digital camera, you will feel right at home with the metering as long as you are shooting shutter or aperture priority. Shutter speed and aperture can be adjusted only in half stops though. I dig that, but if you rely on third stops from your digital camera, it might be annoying.

Max shutter speed: 1/2000. Fast enough for most daylight uses. Depending on your lens’s maximum aperture and the film speed you are using, you might not be able to shoot wide open on sunny, bright days.

Flash sync speed: 1/125. Not that far from many modern digital cameras and fine for studio/indoor work.

Film advance and rewind: It’s all automatic and painless and pretty quick.

User manual: I know, I know. Photographers don’t ever read instructions, but you’ll likely need a manual for these older cameras, especially if you don’t have much experience with film gear. There is just too much weird stuff to figure out. Luckily, Canon hosts a comprehensive Camera Museum where you can download a pristine PDF of the EOS 650 guide.

History of the EOS 650

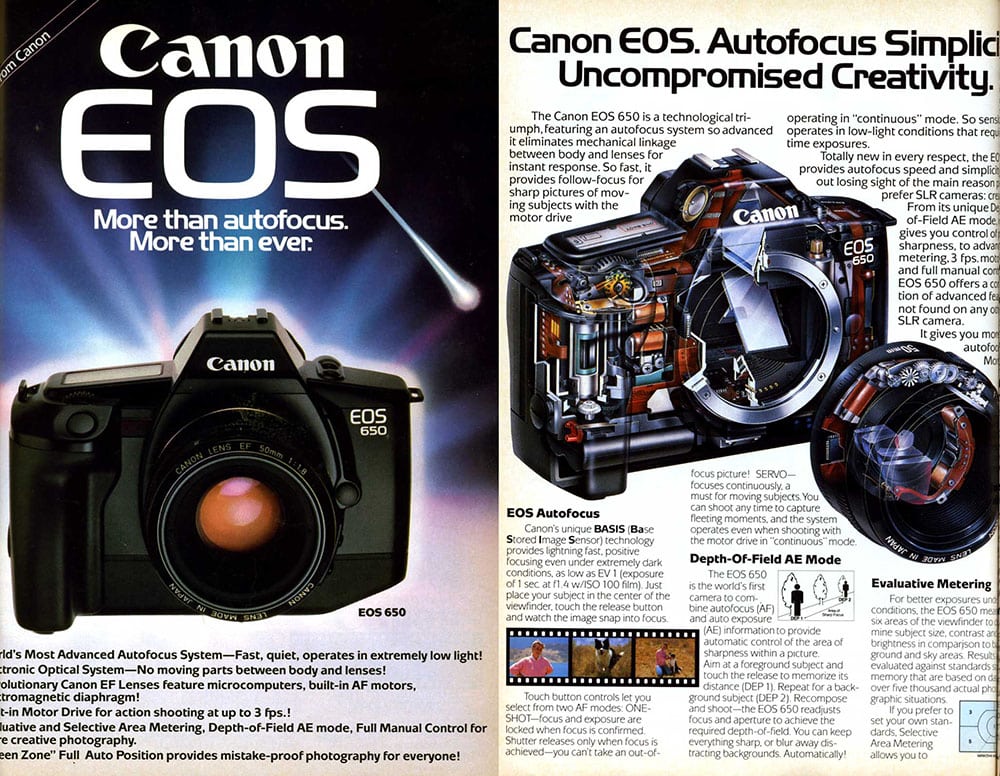

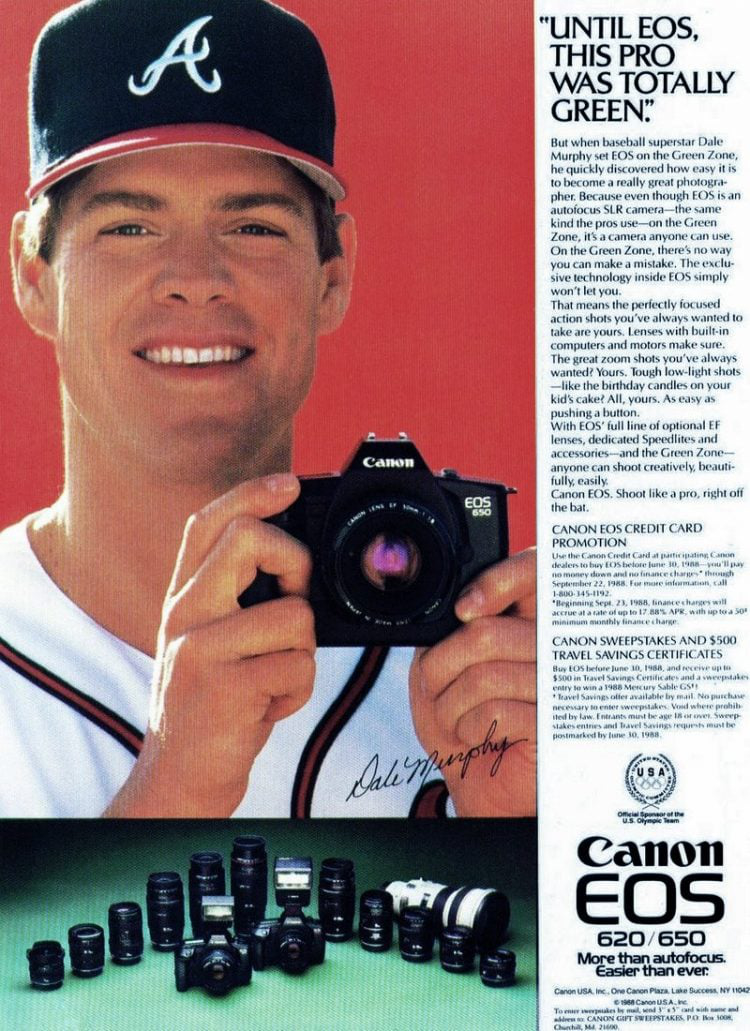

Up until 1987, Canon was second place in the SLR pro market to Nikon. Autofocus at that time was in its infancy, so pros wouldn’t go anywhere near it. Canon realized that its then-current FD mount, which it had invested a lot of time and money in, wouldn’t be up to the challenge of providing the best autofocus experience, so the conservative company did the most forward-looking thing in its history: it ditched the FD mount and came out with what we all know as the EOS EF. The mount is special because the focusing motors are in each lens itself, not the camera’s body. It’s super quick even now, but back then it was a revelation. Canon pros at the time were furious because they had also invested so much time and money into the FD mount, but they and a whole bunch of Nikon users were eventually won over. Canon to this day dominates in the pro sports market.

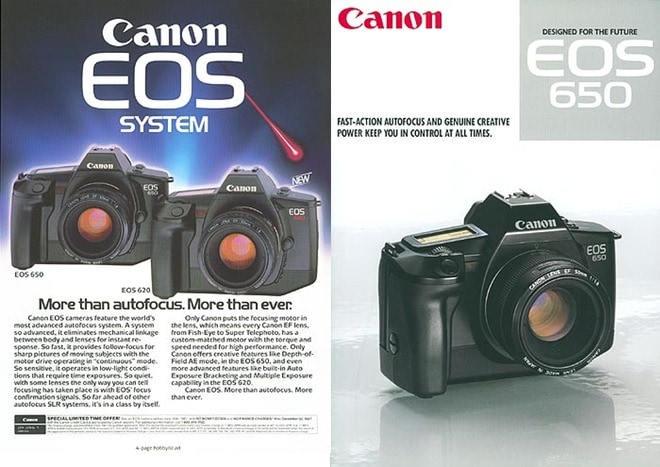

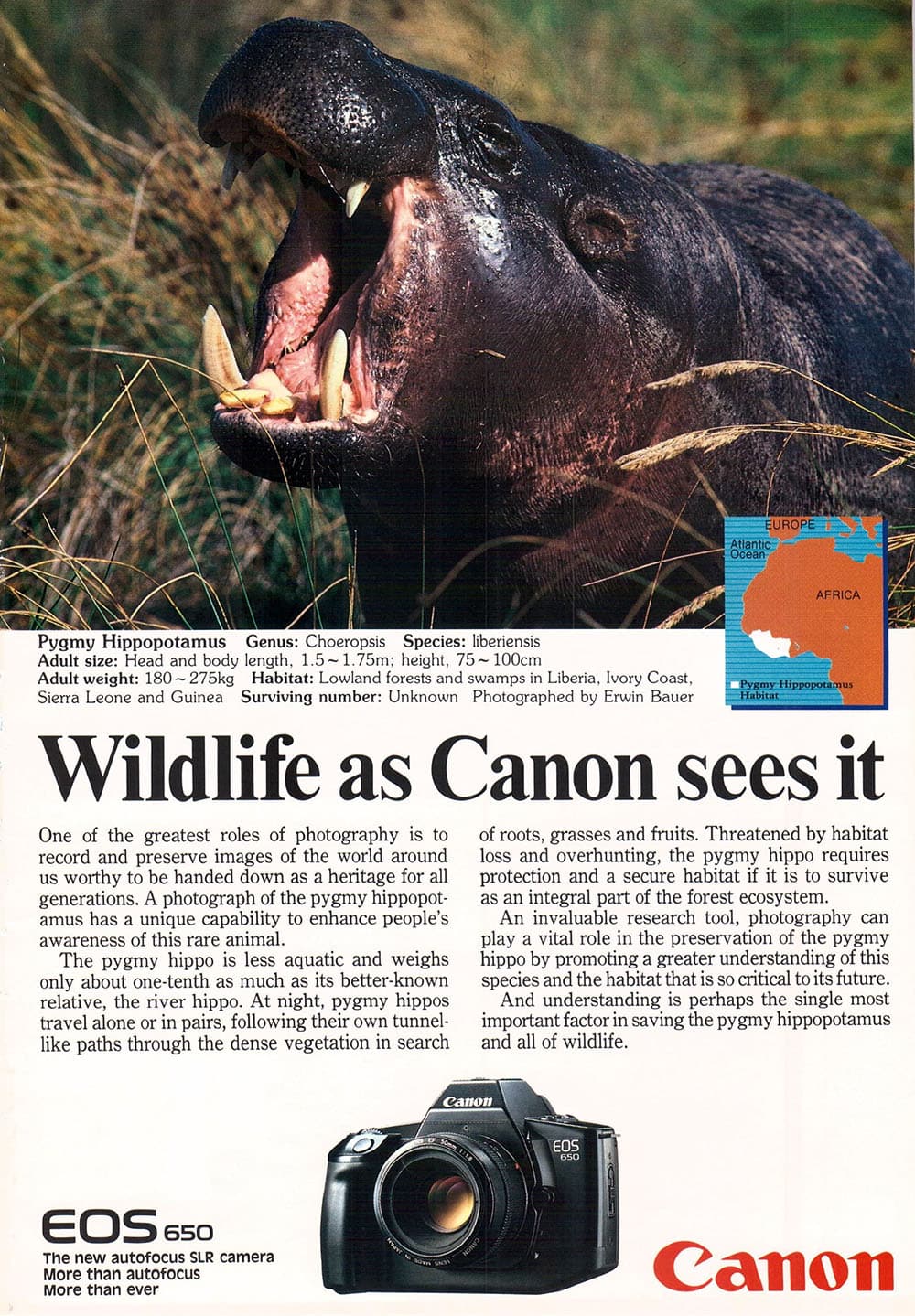

In March 1987, the mild-mannered EOS 650 was introduced as the first Canon camera with this new mount. It’s at best an enthusiast camera that would be surpassed by the EOS 620 a couple of months later, but all of us Canon shooters owe a hat tip to this first comer that was “designed for the future.” Check out the subtle ‘80s marketing material.

Me and My EOS 650

But I didn’t know about any of that history stuff when I purchased my 650 seven years ago. I was simply looking for a more modern 35mm film camera than the one I had, a manual-focusing Minolta XG1. At the time, I was also really interested in having printed images that were produced on 35mm film; the actual process of making them—the tactile experience of manually advancing and rewinding film, of selecting shutter speed on a dial or aperture on the lens—was something I already had with the Minolta. Instead, I wanted something faster, something more akin to the experience of shooting on digital but with the end result of an image printed from film. Because I was already shooting with a 7D and had a handful of EF lenses that I really liked, the 650 seemed like a good fit for the gear in my bag and the money in my wallet.

And in truth the camera was. On music gigs, I’d throw it in the bag with a cheap 50mm f/1.8II attached and loaded with Ilford 3200. After digitally getting all the shots I needed for the job, I could grab the 650 and just have fun. If the pics sucked (and they frequently did…my fault, not the camera’s), it was no biggie because I knew it was playtime.

If that sounds like the camera is merely a toy….you are not totally wrong. For me, the 650 is at best an incredibly capable and quite fun toy camera because of its quirky and ultimately useless manual exposure mode. If you can’t put and use a camera in manual, it just ain’t…a serious camera. For my needs anyway. You can judge for yourself after we dive into the 650’s quirks.

Battery Access

Unlike a lot of film cameras, the EOS 650 thankfully uses a still-pretty-easy-to-purchase battery, the 2CR5. Unfortunately, though, the camera’s battery compartment isn’t as easy to access as the one in a modern digital camera. You first have to unscrew and remove the 650’s grip. I use a quarter to loosen the screw, and it looks kind of stupid and is kind of cumbersome, so I wouldn’t want to do it during anything critical or when clients are around. Happily, a 2CR5 battery lasts quite a long time, especially if you are running only a few rolls of film a month through the camera, so you could easily go a year before needing to replace the battery.

Turning the Camera On

The main switch has four positions, three of which might not be clear if you are coming from a modern digital camera.

- The L position means the camera is off. Some users have said the letter “L” here stands for “Lock.” Makes sense I suppose. When it is in this position, you can’t take a photo.

- The A position means the camera is on and can be used to take a photo. It will not beep for focus confirmation though.

- The third position looks a bit like a Wifi symbol. When you select this, the camera is on, and it will make a short beep when focus is confirmed and a long beep if the shutter is too slow to eliminate camera shake.

- Finally, there is the green square position, which is still commonly used today for full Auto. If you select this, the camera will make all the decisions for you, including shutter, aperture, and one-shot mode.

Loading Film and Checking the Shutter

Loading film is a quick process with the 650. Pop open the back cover, stick in the canister (with the tapered end down), and stretch the film until the lead reaches the orange mark. Make sure one of the sprocket holes has a sprocket tooth in it, and close the cover. The film will automatically advance for your first shot, and the ISO will be automatically set if your film has a DX code (most today do). The back cover also has a handy little window that shows what type of film you have loaded.

While you have the back cover open, check your shutter blades. According to forum chat, aged 650s appear to be pretty plagued with sticky shutters because the shutter bumper can melt and deposit goo on the blades. They can apparently be cleaned by using Q-tips with alcohol or lighter fluid, but I can’t vouch for that because I’ve luckily never had to do it. My shutter blades are looking a little worn though.

Rewinding Film

The camera automatically rewinds the film after you take your last shot. What your “last shot” is depends on what the film’s DX code indicates—that is to say, even if the canister technically has more film available, the camera will begin rewinding after the 24th or 36th (or whatever-th) exposure is made. No squeezing out extra shots with the 650.

The autorewind is pretty quick. It takes about 12 seconds to complete a 36-exposure canister. Once the film begins rewinding, the display panel shows moving bars and counts down the remaining number of frames. It’s oddly satisfying.

Hidden Stuff Behind the Flippy Door

Below the film cover on the back of the camera is a small door that flips open to reveal four more buttons. From left to right, we have the following:

- A film rewind button. Press this if you want to rewind your film before you finish the roll. It will automatically begin rewinding. I’ve never actually pressed it (because who wants to waste film?), but I assume it rewinds as quickly as the usual way.

- Next, is a yellow autofocus selector button. It allows you to toggle between one-shot and continuous focusing modes. Press the button and then rotate the shutter button to select each mode.

- Then there is a blue button that allows you to set the camera’s film advance settings: single shot, continuous shooting, or a self-timer. The max frame rate for continuous shooting is 3 frames a second. The self-timer is for 10 seconds.

- Press both the yellow and blue buttons to manually set your film’s ISO. You’ll need to use this for sure if your film does not have a DX code.

- Finally, there is a battery check button. If you press it and “bc” blinks on the top LCD, the camera is malfunctioning. Before, however, you take it in to a repair shop (or simply throw it in the trash and buy another one), take out your battery and clean the battery contacts with a Q-Tip. Dirty battery contacts often trigger a camera’s malfunction warning. Always, always check battery contacts if something is amiss! Doing so is a super easy and quick fix.

Quirky Manual Exposure

There is no other way to say it: shooting manual exposure on Canon’s 650 is weird and sucky and ultimately useless. Changing aperture is cumbersome, and manual metering is flat-out bizarre.

Once you put the camera in manual mode, you change shutter speed in the usual way by rotating the dial on the camera’s grip. There is, however, no designated, exclusive aperture dial. To change aperture, you have to press and hold a small button on the side of the lens mount (where the depth-of-field preview button is on modern cameras) and then rotate the shutter dial. You can only change one or the other at a time. Here is what the aperture button (designated with the letter “M”) looks like.

So changing aperture on the 650 means that you have to constantly change your hand position and grip the camera awkwardly, which isn’t at all speedy or ergonomic. The camera essentially forces you to become a slow and stupid wobblemeister who shoots mostly missed moments that are blurry.

But that isn’t the end of the manual misery. Metering for manual exposure uses a needlessly cryptic set of letters to indicate under- and overexposure.

- “OP” means the shot is underexposed. You have to, as the manual says, “OPen the aperture.”

- “oo” indicates a correct exposure.

- “CL” means the shot is overexposed. You have to, again as the manual says, “CLose the aperture.”

Painfully lame, yes? To make it even worse, there isn’t any indication of how under or over you might be. To make it even doubly worse, you need to press and hold the aperture button for the camera to show a meter reading. Because metering isn’t constant, you can’t adjust shutter or aperture on the fly and see the results of your adjustments.

Canon, in short, (mis?)designed this camera to be shot exclusively in an automatic mode, and the only way you can possibly get on with the 650 is to embrace its intrinsic auto-natured-ness. Mine lives and will eventually die in aperture priority. Once I accepted that, shooting the 650 became a fun experience.

Mode Button Kudos

Most current digital SLRs have a big dial on the top of the camera for switching among the AV/TV/Program/Manual modes. The 650 instead uses a simple and space-saving button inherited from Canon’s final flagship FD-mount camera, the T90. It’s the same simple setup that the later pro-level 1 series cameras, both film and digital to this day, would inherit as well. I totally dig it. I’ve never understood wasting all that physical space for something that isn’t really changed that often. And even if a shooter does like to toggle between modes quite a bit, using a button and the shutter dial is just as quick.

Should You Buy a Canon EOS 650?

Knowing what I do now, I wouldn’t buy one again, but it might be the right camera for you if you fall into one (or both) of these two specific cases:

- You don’t have a ton of cash and you already shoot with a Canon digital camera and a collection of EF lenses. You really want to give 35mm film a go, and you want the experience of using a film camera to be pretty painless, so it needs to have autofocus, modern(ish) metering, and automatic film advance and rewind. Most important, you live in aperture or shutter priority, and truly love living there. A 650 is absolutely not the right camera if you shoot in manual and/or want the “authentic” film shooter experience of manually focusing and manually advancing/rewinding film.

- You are a camera collector or a Canon completist. The 650 is historically important and interesting enough to own, and it’s cheap enough to inoffensively do nothing but shelf duty in a dusty collection.

That said, an autofocusing, fast-loading 35mm camera is still definitely a viable option in your gig bag if you want to shoot and produce film. Instead of the 650, the better Canon alternatives are the pro-level EOS-1 or EOS-1N (or ideally the 1V if you can swing the big cash premium). My lightly scratched 1N cost $175 three years ago; the extra hundred bucks over the 650’s price was totally worth it to me, and I suspect it shall be to you too once you shoot with one.

Comments

Nice review! My dad passed away in 2005 and I found an EOS 650 in his photo bag, many years later. I guess he bought it new in 1987 and only used it a few times. The camera came with a lovely 50mm f/1.8 and 35-105/f3.5-4.5, which attracts me less.

Given the both historic and personal value, this camera will be a special item in my collection of MF Minolta’s and Praktica’s. I am due to use it with film, though. So far, all buttons and gadgets seem to work fine and compared to the Minolta 7000, which started the true AF-ratrace in 1985 imho, the camera is 250% easier to use and so much better built.

It will be the one and only AF-camera to use for film, for me. 🙂

I started using an EOS 650 a few days ago. Since I already have a ton of EF lenses it was a natural choice. I’m not finding the full manual to be that daunting, though a big, heavy lens is going to make the ergonomics of reaching for the M button difficult. But if I have something like an f/1.8 50mm on there it’s not too bad, and I’ll be proficient with it with a little bit of practice.

Before some years I bought a used canon 50mm 1.8 lense. It was in a bag with a canon eos 650 for free. How sharp lense is this 50mm! Now I search a similar sharp one but a little more wide angled, like 28 or 35mm. From your experience which one do you think is sharp enough to have with the classic 50mm?

In my experience the 28mm f2,8 is very sharp.

[…] Camera Review – The Autofocus Revolution Arrives Lomography – A Review of the Canon EOS 650 Scott Locklear – Canon EOS 650 Camera Review Down the Road (Jim Grey) – Canon EOS 650 […]

I love the 650.

I had a 6 lens set of fully manual zeiss ZF (adapted to EF) lenses sitting around which I previously used for cinematography before graduating to PL mount. And I was just looking for a film camera that would accept EF. To my suprise the 650 was $24 (including shipping) in immaculate condition.

The auto nature doesn’t bother me. In fact coming from a bunch of older film cameras like the F3, xrt101, k1000, 35rc,

I really appreciate it.

I just choose my stop on the lens and let the camera choose the shutter and I can easily adjust as needed. That’s how use my fujis. I honestly don’t see the purpose of ever shooting full manual on any modern camera. I can still make those choices but let the camera calculate faster. That’s just me though. I’d rather put my attention towards the focus ring when a moment presents itself.

This camera really stays out of your way and even in full manual I find it super accessible. But perhaps that’s because my lenses have aperture rings.

For anyone with fully manual EF lenses looking for a cheap and reliable camera, it’s a solid choice. Take advantage of camera depreciation and put your money towards nicer glass.

That said, if you have auto lenses (like the author), and you want to shoot in manual… then yeah, perhaps not the right camera for you.

Great job reviewing and thanks for sharing. I’ve used a 630 model thru the 1990’s, specifically since 1990 till I got a Nikon N80. Been to east Berlin in 1991 just following the falling of Berlin wall, been to Capricornia Islands off the east Australian coast. The 630 never failed me and delivered outstanding performance. Until about year 1998 when I discovered that the battery started to die more quickly than usual. Towards the end, two days in OFF position would drain a new battery. That was one of the reasons I made the switch to Nikon. Recently I found out that the 630 was an improved version of 650 and it had an illumination feature of digital readout added to it over the 650. That apparently is the reason of the problem and there is a quick fix for it by cutting off some wire inside. Or else to remove battery altogether when not in use. I recently bought another 630 and it also has the same problem, so I will look into making a permanent fix on them. Overall I just love the design of that first EOS body, especially the undercut on LH side. One thing to remember, is that Canon made the shutter mechanism electronic and virtually bulletproof in terms durability and timing accuracy. None of the earlier “sheet metal” body cameras from Canon, Minolta, Nikon or Olympus can hold a candle to the shutter accuracy and I’ve measured many of them myself. All the best.